Historical reference (in less than 30 mins)🔗

Historically it happened so the UI side of websites is split into 3 technologies: markup - HTML, styling - CSS and code - JS. This separation is one of the first things newcomers to web learn. I remember I was briefly introduced that it is possible to write both CSS and JS right inside HTML, but we quickly concluded it is a bad practice because of separation of concerns: markup, styling and code should be kept separate to keep stuff in order.

The first somewhat real code I wrote in the college was Ruby on Rails, which followed MVC architecture. The first job position I landed was front-end developer with Angular as a main framework, Angular follows MVVM architecture. Both MVC and MVVM can be fairly considered a classic examples of separation of concerns: models are separate from views, views are separate from controllers etc… Angular additionally keeps HTML/CSS/JS files of the same component separate by default, which aligns perfectly with what I initially learned.

At some point of time I get acquainted with Atomic Design Methodology, which also splits the components by their technical characteristic: if component is simple - it is “Atom”, then based on increasing complexity there can be “Molecules”, “Organisms”, “Templates” and “Pages”. Component with higher complexity can use components with lower complexity, but not otherwise. I concluded that it is the common way to structure modern design systems.

From the other side same Angular I talked earlier introduced me to “Folders-by-feature” principle in its official style-guide. Later I found that it has a little bit nicer name outside Angular ecosystem, it is called “Vertical Slice” (as opposed to “Horizontal Slice”, that is followed by MVC and MVVM). According to it project files shouldn’t be grouped by a some technical trait like “keep all components together” and “keep all services together”. But rather by its feature or domain of use - all dashboard-related stuff should be kept together disregard of whether we are talking about components, services or whatever else. I really liked this approach and didn’t notice the contradiction with what I already learned.

At some point of time I needed to dive deep into Angular Material source code and it was my first time digging into huge open source code-base. It didn’t follow the Atomic Design Methodology, but instead more or less grouped the files by their respective domain. I still didn’t pay enough attention. After all Angular Material itself doesn’t follow the official Angular style-guide, so it may also branch itself out from “industry standard” e.g. atomic methodology.

Last year I started to play around with mobile development. Since I have an iPhone and my wife has an Android, I needed to go with cross-platform solution. I chose to learn Flutter and Dart. There is no separate technology within it for markup, styling and actual code. Everything is code, everything is Flutter. It felt wrong in the beginning, but with time I got a moment when I realized, that having a type-safe markup and styling is a huge boost for both productivity and developer experience1.

Recently I watched the documentary about React. Also I heavily use Tailwind for the blog you are reading right now. Both those technologies are accused of violating separation of concerns principle: React merges markup and code by leveraging JSX, Tailwind puts styling back into markup. But this time it didn’t feel wrong. I finally succeeded to switch my mindset and understand why it is even better separation of concerns that what I learned initially.

”Concern” is not technical term, but a logical one🔗

The common way to explain OOP is using real-world analogy, in particular via biological classification of organisms:

abstract class Animal {

abstract move(): void;

}

class Mammal extends Animal {

move() {

// Move in 2d space

}

}

class Ave extends Animal {

move() {

// Move in 3d space

}

}

class Dog extends Mammal {}

class Crow extends Ave {}You have a most abstract class of Animal, which is distinct from Plant. Then you have two classes of Mammal and Ave, which are distinct from each other, but both inherit from Animal. Then you have a Dog class as a most narrow example of Mammal and a Crow as a most narrow example of Ave. This analogy allows developers to structure the code in DRY and well-organized manner. For example a common thing between all animals is that they can move, so the abstract class Animal can define abstract method move, then Mammal can implement this method considering that mammals walk and Ave can implement this method considering that birds fly.

Everything is nice and clear until we step out from programming courses and tip our toe into real world software especially frameworks. The abstractions I see there are: models, views, controllers, directives, components, services… WTF?! My kitten Nami doesn’t consist of separate CatService, CatController and CatComponent abstractions spread throughout the entire apartment. At this moment I gave up on the examples from learning courses and went along with abstractions of real world software. But now I’d like to stick with it, but with an asterisks.

There is a well-known issue with inheritance in OOP: each new bottom-level candidate might introduce a change that leads to a full refactor of the whole inheritance chain. In our example with Mammal and Ave we concluded that mammals walk, aves fly. But what about bats and penguins? We didn’t think about cases where mammal can fly and bird can swim, why would we? The required bottom level classes of Dog and Crow fit well with our initial hierarchy, but apparently this hierarchy is not scalable or flexible enough to serve us in the long run.

Here comes another programming buzzword - composition.

interface Walkable {

walk(): void;

}

interface Flyable {

fly(): void;

}

class Dog implements Walkable {

walk() {

// Move in 2d space

}

}

class Crow implements Flyable {

fly() {

// Move in 3d space

}

}Instead of defining deep chain of different classes we define the bottom-level set of candidates that we need (Dog, Crow) and set of traits or skills that we can attach to them (Flyable, Walkable). This way each new bottom level candidate (Bat, Penguin) can take traits that it needs or introduce a new one (Swimmable) without forcing existing stuff to be changed.

Now back to real-world programming and my lovely kitten. This way in the program I can have Cat abstraction as a single directory that has some digital characteristics like CatService, CatController and CatComponent as files within this directory just like in the real world it has physical characteristics of Walkable, Talkable and so on.

I consider this way of structuring the code is way more intuitive and easier to understand, but it comes with a very important mental switch under the hood: the concerns we are separating are not CatComponent from CatController, but CatComponent from DogComponent. The tech categorization comes after and only after logical categorization. On a low level it means markup, styling, code are not a concern since they are technical traits, component is a concern. On a high level it means components, directives, services are not a concern because of the same reason, the dashboard, settings, news feed are a concern. You first separate with vertical split, and only after it with horizontal split.

Benefits of vertical split mindset🔗

It all sounds good and everything (I hope so), but what’s the point, yeah?

Less mental overhead🔗

Let’s say you are in a huge back-end project having 100 resources. Each of those resources is a REST endpoint, so it consists from at least 3 type of files: route API handlers, business logic services and data access layer models. If you make horizontal slice you have 3 folders with 100 files in each one of them, if you make vertical one - 100 folders with 3 files in each.

Now you have to add a new resource. While developing with horizontal split you need to constantly jump between 3 directories full of other files irrelevant for your task, but with vertical one you scoping down your work to 1 directory with only 3 files. Less white noise you have easier the work goes.

But it doesn’t end up with developing only. Now let’s say you developed resource A, that led for changes to resource B, that already existed in the project. You finished your changes and send it to your team for code review. The order of files your team sees in PR is the following:

- new route handler of resource A

- updated route handler of resource B

- new business logic service of resource A

- updated business logic service of resource B

- …

Which makes not only you jump in between different directories during development, but also all the people who needs to review your code. There is no option to first go over all the resource A changes and then go to resource B stuff. I worked in projects with horizontal split structure. During the review of my code I personally saw team lead constantly jumping over a bunch of resource B files just to get to next resource A file. He didn’t see it as problem, but I saw it caused him to struggle to get the full picture of this PR. Wouldn’t it be way more convenient if the order of files for review would be like this?

- new route handler, new business logic and all of the stuff related to resource A

- updated route handler, updated business logic and all of the stuff related to resource B

Scalable out-of-the-box🔗

When we lay down the foundation of the project we want it to scale to 1m users with ease. Usually it means the following: micro-service event-driven architecture with load balancing deployed in cloud native technologies with zero down-time available across the globe ©️. In real world you either never finish the MVP of such or you make a lot of shortcuts only to find yourself in huge tech-debt after a while.

It comes so because all those fancy words come with a price: system complexity. Huge scalable systems not only serve a lot of users, they are meant to be developed by a lot of engineers. From the other side good old monolith can rocket-boost your MVP in less than a week. But after you get your VC money and the project gets first somewhat serious traffic it’ll face its performance ceiling and it won’t be easy task to split it into smaller standalone parts. Don’t forget about talking your investors into spending half-a-year to do the refactor without increasing the margins in the meanwhile.

I do believe that vertical split allows to get the best of two worlds. You develop a monolith at first as fast as you need. But since you have 100 folders with 3 files in each and not vise-versa when the moment comes it is easier to take 50 of those folders and put them into server on its own. Furthermore since you put the logical boundaries first it is less likely for anyone to mix things up along the way. Everybody knows not to mix controllers with models, but keep project-specific logical abstractions in the right order is way harder. Vertical split forces us to not shortcut the essential architecture.

Unit tests aren’t nightmare anymore🔗

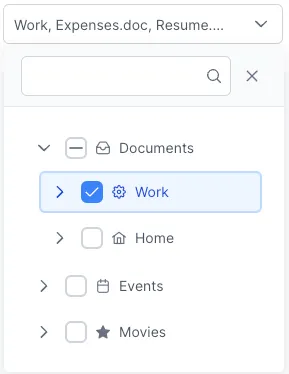

During one of the job interviews I was having recently I got home assignment to build the following component. It is a tree select dropdown with option for a single and multiple selection mode and option to filter leaves. As part of the task I was asked to cover one of the component entities with unit tests. The framework is Angular.

The final solution included 1 component, 5 directives, 1 pipe, 2 services and 2 non-standard file types. The classic unit testing means you identify a minimal standalone unit inside your program, mocks/stub all the other and test behavior of the chosen one. In my example it can be any of the mentioned above entities since each of them is technically standalone. Mocking/stubbing is always a painful part in unit testing, because you as a developer don’t develop anything, you don’t add value to the product, you just making endless preparations to code the thing that should add value.

Here I caught myself once again thinking in technical terms instead of logical. Nobody argues that private methods shouldn’t be covered with unit testing, right? It causes too strong coupling of tests with actual code. Only public part that is meant to be used should be guarded. This principle while being grounded in technical terms of “private” and “public” actually talks logically: test covers the surface of the unit without going any deeper. Components, directives, pipes and services are technical Angular terms, the surface is what user of the component uses and in this case it is 1 root component and nothing more. So the candidate for the test coverage became obvious and nothing should be mocked, since logically it is one single unit.

You might say it’s not a unit test, but rather integrational one, because it touches several entities and theoretically user can access other internal entities. But I don’t think so. Imagine language or framework provides you with the option to keep stuff “private” while simultaneously split it into several different entities. Would you cover each entity with its own set of tests or would you cover with it only the part that is meant to be public by the definition of the feature?2

We shouldn’t obey technical restrictions of our tools: just like “concern” is not a technical term, “unit” also not of this kind. Understanding this reduces amount of boilerplate and allows our code and test be more meaningful.

Outro🔗

While I do see this pattern in a lot of technologies today, overwhelming majority of them isn’t developed by one person with one mindset. As a result we have React unified technically different HTML and JS into JSX, but then came NextJS with all other meta-frameworks and introduced purely technical distinction between different components with file-based routing… Angular itself preaches “Folders-by-feature”, but decided to keep markup, styling and code separate, because it wanted to achieve a more vanilla-like web-experience for its users…

After all nothing is perfect and is never meant to be. “Good enough” is our industry slogan, thats for sure. But having a right mental model as well as unlearning harmful parts of college education is a way to care for yourself during the activity, that takes almost as much time as you sleep. Now I have less chance to shoot myself in the foot, wish the same for you.

Footnotes🔗

-

Imagine you have LSP for the CSS shit like text-overflow: ellipsis; or text-decoration: none;, that can instruct you which exact combination of rules you need to use to get what you want. Imagine you have LSP autocomplete for only relevant CSS properties on a target HTML element without leaving your IDE. Imagine you don’t need to wait for a good Can I use score for CSS3 variables nor go with SCSS to get reusable styling values. This is what you get when markup, styling and code are not separated. ↩

-

Dart allows it with partial files by the way. So there you can keep files within reasonable size as well as keep right level of encapsulation. ↩